| ||||||

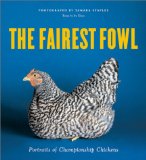

A few good chickens,

fashion-plate birds

By CAITLIN DIXON

Tamara Staples photographs a beautiful chicken.

Take the bird looking out from page 39 of her new book The Fairest Fowl: Portraits of Championship Chickens. He's a "Bearded Buff Laced Polish Large Fowl Cock." This name — long, insistently specific, yet somehow poetic — is typical of the birds featured in Staples' elegant portraits. The book's text describes him as "poultry royalty," and indeed his beautiful golden feathers settle around his shoulders like a mantle, and an astonishing burst of feathers about the head suggests a crown, or perhaps a lion's mane.

But it is the chicken's expression that is the most striking. He turns his head from the shadows of Staples' dramatic backdrop, with wide-set, heavy-lidded eyes, and beak set high up in his face like a disapproving sniff. It's unsettling. You get the sense that, if this bird had thumbs, none of us would survive the gladiator's ring.

It's this surprising expressiveness that Staples excels at capturing in all the championship chickens she so lovingly portrays. Each bird is shot like a movie star, lit dramatically against rich, colorful backdrops.

"I had been profoundly inspired by this still-life photographer I was working for," Staples says, explaining the germination of the chicken portrait project, back in the early nineties. "The objects, the backgrounds she would use ... it was just lush. It was sensuous. The color and the light and everything, it created a story." So, when Staples decided to photograph at the poultry shows that her Uncle Ron frequented with his prize Bantams, it was this luxurious approach to chickens that she intended from the start.

Not that it was easy at first. "The first two years I went out, I didn't get anything," Staples recalls. "I lit it, you know, and I didn't even know anything about lighting. I would borrow bits and pieces of equipment, and sometimes it wouldn't work. I was using things like country fabrics as backdrops. Like burlap sacks, or browns, or white paper." The opulent backdrops that became the signature of these portraits didn't evolve until her friend Dennis Ayuson, a photography assistant himself, brought several colorful backgrounds along on a shoot.

"That's when it finally all came together. You know, I can't take credit for all of it, as much as I'd like to." Staples laughs. "I experimented with a lot of types of different types of equipment. I bought a new lens during this time. I started figuring out how to light them at their best. And how to hold them, and touch them, and get them to do what I wanted."

But the expressive shots that adorn her book were not the goal of her initial shoots. "When I would get home, my first impulse would be to pick the bird that closely matched the Standard of Perfection," Staples says, referring to the hand-painted guidebook that chicken breeders use to judge their birds. Standard of Perfection birds are invariably portrayed in profile, chests out, tails up, chins — such that chickens can have chins, that is — high. "But then my friends would be like, 'Oh, look at how he's looking into the camera, how he's looking over like this, or look at how she's squatting down on the background: That one's really funny.' And so it just evolved, again. Once I saw how great these were, I started making editing choices based on that."

But though abandoning the Standard of Perfection poses allowed the quirky flashes of personality that make Staples' portraits so interesting, that very Standard is what breeders aim for, and what they want to see. "A lot were very skeptical," she admits. "They would look at the pictures and they saw the defects of the birds. So that was kind of hard. I mean, I never won them over. But I did my best to show them that I loved their birds. I wasn't trying to say, 'Oh, I can make something out of these birds that you never thought of.' I just wanted to make them beautiful."

Chickens? Beautiful? Well, yes. The birds are beautiful. There is no irony here. Yes, the pictures are often quite witty — seeing a bird with a mournful, or macho, or world-weary expression is surprisingly charming — but that is not the primary intention. "I'm not interested in making fun, you know? I look at someone who does that and I feel like they're exploiting the subject matter."

Staples pauses, reflecting on this idea. "I guess, probably, it's that I'm sort of the underdog. I grew up the nerdy one, we moved around, I was very shy, didn't feel like I was important, was very low on self-esteem. So I wanted something that no one respected — chickens — to seem bigger than life. I wanted to bring dignity to it."

Northeastern Poultry Congress 2009

Photos by Tamara Staples

note: this is a portion of an article copied from http://www.fotophile.com/200112staples.html

Click the thumbnails for a larger view